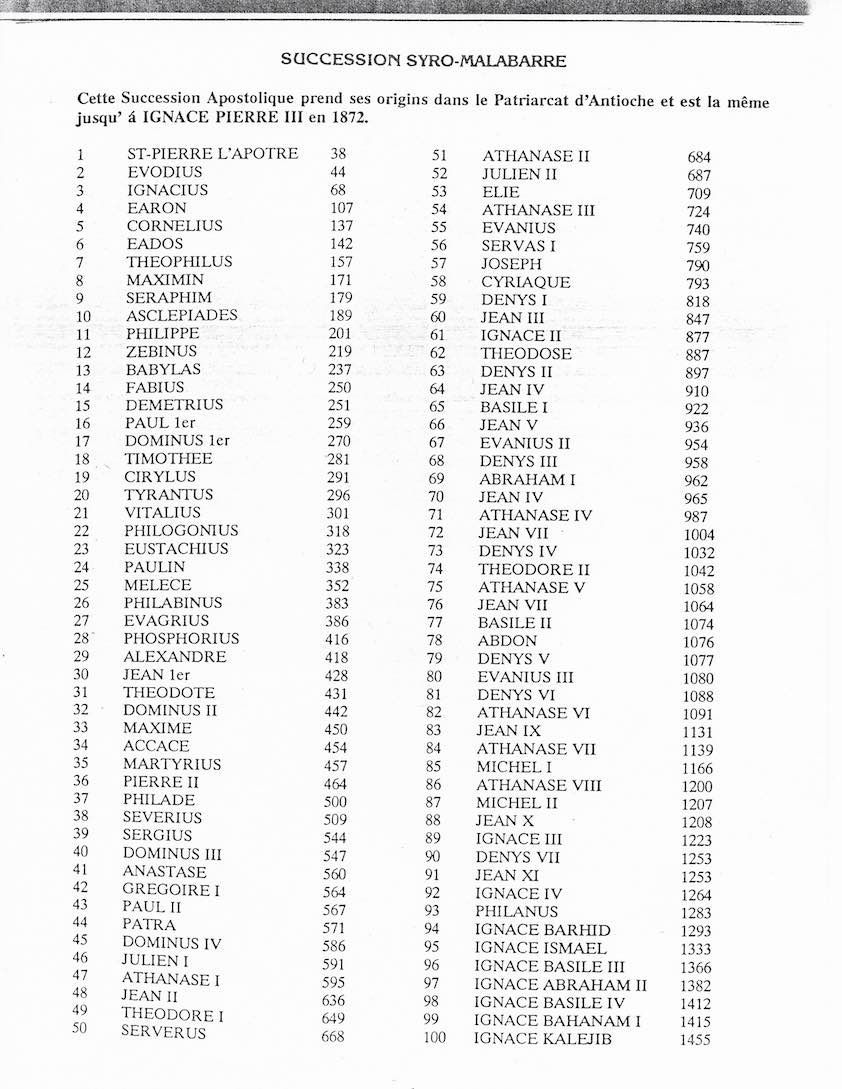

The Syrian-Malabar Succession

The Syrian-Malabar succession traditionally descends from the missionary preaching of the Apostles Thomas and Bartholomew in India. Although the historical accuracy of this claim cannot be fully verified, recent evidence points to an ancient community of Indian Christians previous to the second missionary sweep of the Nestorians. Cosmas Indicopleustes, an Alexandrian merchant of the sixth century who had no particular axe to grind, says that he found Christians in India about A.D. 550.

This is too early for a settled community of Nestorians. On the tomb of St. Thomas in India is found an ancient cross with inscriptions. The inscriptions are made in a form of the Hindu dialect that stopped being used after the second century. It seems likely that the St. Thomas Christians of India preserve the authentic Successions of the Apostles Thomas and Bartholomew.

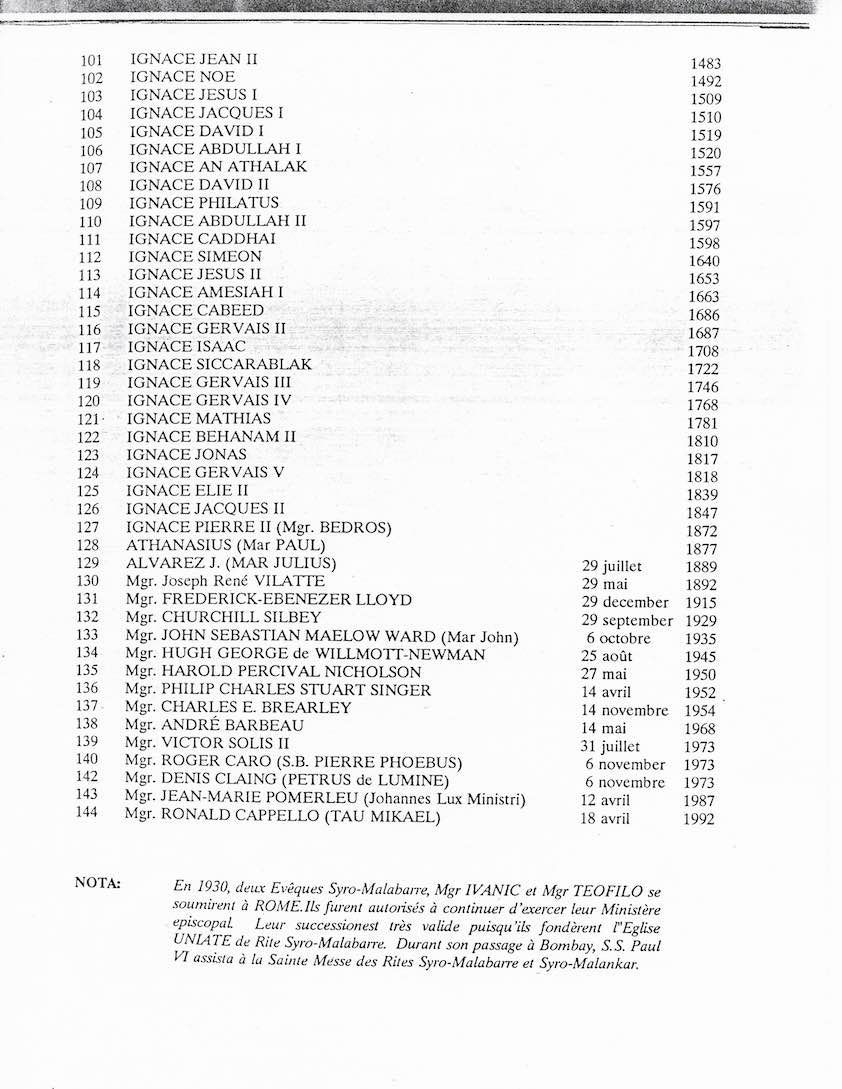

The persecution of Bishop Nestorius and his followers led to another religious revival along Monophysite lines which produced monasteries and missionaries. In the sixth and seventh centuries Nestorian Christians began to flourish in Egypt, Persia (supplanting Zoroastrianism), and finally into China. Coming by way of the sea, Nestorians landed in Madras and joined existing Christian communities of South India. In A.D. 1490 they received new Bishops from the Patriarch of Bagdad, and a continuous contact with Syrian Christianity was maintained from the advent of Nestorianism. However, during the later period the orthodox-leaning Nestorians were assimilated into the Malankarese Uniat Church, while still using the Liturgy of Addai and Mari. The Jacobites survived, and have developed a rapprochement with the Church of England, due to 19th-century colonial expediency.

Through both the St. Thomas Christians and the later Nestorians, valid Apostolic Succession was established in India and other Asian locations. These traditions and their lineage holders survive into modern times, and their Apostolic lines of Succession have been assimilated by most contemporary Independent Bishops.

Similar stories could be told about many other Third-World church traditions with valid lines of Apostolic Succession. They all involve a formative period of apostolic founding, a later period of conflict during which one or several native Bishops were excommunicated or denounced by a Roman-dominated synod, and a separated church history much like that of the Greek Orthodox communion. In more recent history all or some of their community has been brought into communion with Rome, some as uniats, some retaining full native authority.